By EHUD ZION-WALDOKS

‘The return-to-work rate for people after suffering a stroke has not significantly changed since the 1970s,” says Dr. Simona Bar-Haim, founding director of the Negev Lab at the ADI Negev-Nahalat Eran Rehabilitation Village in southern Israel.

Bar-Haim is not your typical academic. She has one foot firmly in the field, and one foot firmly in the academy as a member of the department of physical therapy in the Faculty of Health Sciences at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev (BGU). She also founded a start-up based on chaos theory to help people walk after suffering a stroke.

“Many people do not recover enough to return to work or to their regular lives,” she says.

What is more, as the population ages and lives longer, there are more and more people suffering strokes and then recovering only partial functionality. In Israel, 17,000-20,000 people a year suffer a stroke.

Stroke is tricky. While its effects are well known, the best course of rehabilitation to return to functionality is still very much a mystery, to which Bar-Haim and Dr. Lior Shmuelof, also of BGU, have devoted themselves to help solve.

Driven by that impetus to help and by her out-of-the-box way of thinking, Bar-Haim recently set up a translational rehabilitation lab at the rehabilitation village. Translational science tries to find solutions for real-world problems. At ADI Negev, the problems arise from the patients themselves, their doctors and caregivers, and the solutions are tested in conjunction with the patients.

There are several theories why stroke recovery has not progressed since the 1970s and the Negev Lab has been working to test them.

“We believe there is a critical period of three to six months after the stroke where recovery is most achievable because of the brain’s plasticity during that time,” says Shmuelof of the Negev Lab, the department of brain and cognitive sciences and the Zlotowski Center for Neuroscience at BGU. “If an animal suffers a stroke, it recovers fully. Why do animals recover, while people do not? One possibility is that an animal is active from the moment it happens. Now, if a person suffers a stroke, they spend the first week to 10 days lying in bed in the hospital, and then they spend a couple of hours a day doing physical therapy that does not translate to the real world.”

“We believe there is a critical period of three to six months after the stroke where recovery is most achievable because of the brain’s plasticity during that time,” says Shmuelof of the Negev Lab, the department of brain and cognitive sciences and the Zlotowski Center for Neuroscience at BGU. “If an animal suffers a stroke, it recovers fully. Why do animals recover, while people do not? One possibility is that an animal is active from the moment it happens. Now, if a person suffers a stroke, they spend the first week to 10 days lying in bed in the hospital, and then they spend a couple of hours a day doing physical therapy that does not translate to the real world.”

To confirm these hypotheses, Shmuelof is partnering with the MRI Imaging Center at Soroka-University Medical Center and researchers Profs. Alon Friedman, Ilan Shelef, Anat Horev and Gal Ben-Arie, with the aim of identifying the neural components associated with brain plasticity after injury.

Shmuelof will then take what he learns from MRI imaging and bring it back to the Negev Lab.

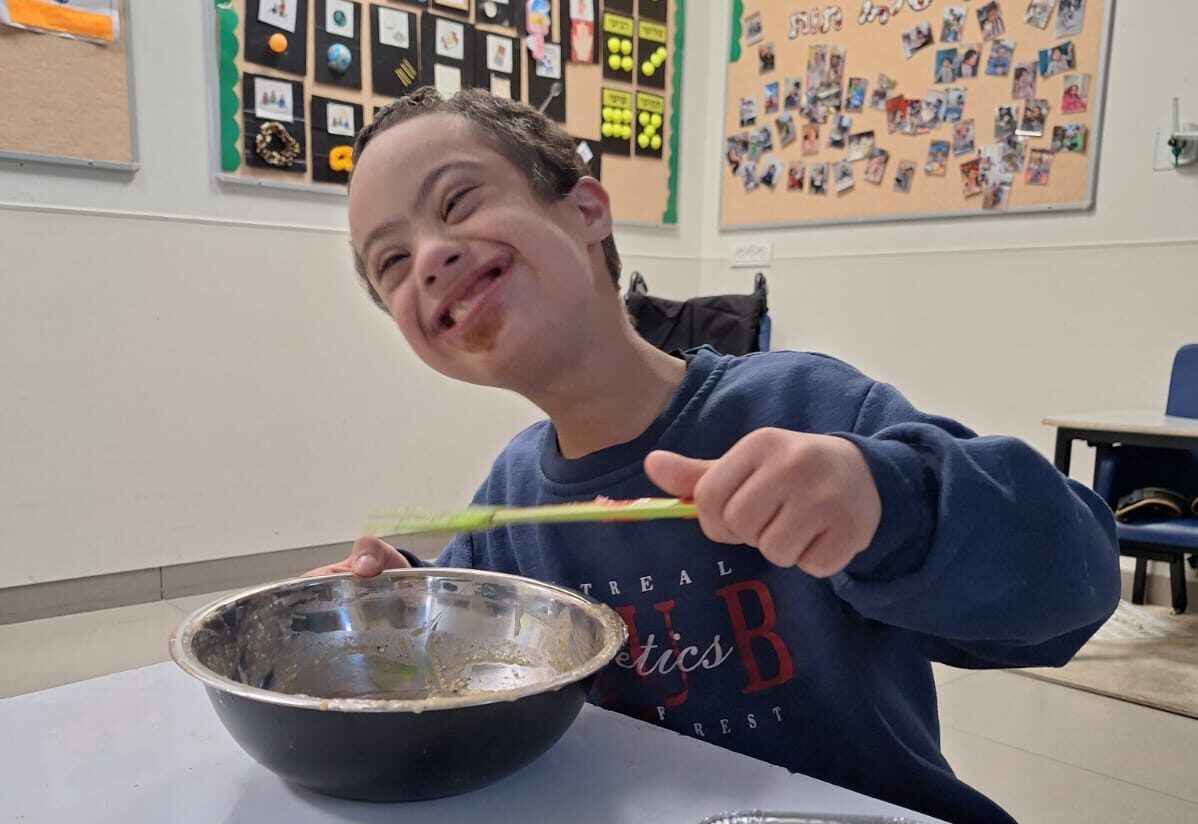

ADI Negev-Nahalat Eran is a fully equipped facility in a village setting, with residential care for people with multiple disabilities and complex medical conditions, an intensive care hospital wing for babies and adults, a paramedical center, hydrotherapy pool, special education school, green care farm, and a therapeutic horse stable and petting zoo.

It is set in an ideal and idyllic location. Winding paths run alongside the residents’ cottages. A stable for therapeutic riding anchors one side, while the Negev Lab anchors the other. The atmosphere is calm, quiet, happy and optimistic – a far cry from rehabilitation wards in large hospitals.

The ADI Negev-Nahalat Eran Rehabilitation Village was named in memory of Eran Almog, the late son of Didi and Maj.-Gen. (ret.) Doron Almog.

Fueled by his love for Eran, who was born with severe autism and intellectual disabilities, Doron Almog guided the creation of a residential and rehabilitative complex in Israel’s south, which has since become a home and family for more than 150 children and young adults with severe disabilities and complex medical conditions and provides a host of rehabilitative solutions for individuals from all backgrounds and levels of need.

While care is important, the vision is to provide cutting-edge treatment as well. The first step was the creation of the Negev Lab. Not far in the future, the village will also boast a rehabilitation hospital, which will be the biggest in southern Israel.

“ADI Negev is the ideal place to see what happens when people spend many more hours rehabilitating,” says Shmuelof. “What if they spend three hours a day or five hours a day? Would they recover faster and better? These are the kinds of questions we ask ourselves and have the ability to answer because of this unique lab.”

Existing movement tracking methods are not advanced enough to meet Shmuelof’s needs. Therefore, to track patients’ motion over the course of the day, the Negev Lab is developing methods to track not just walking but also arm movements.

“One of the things we noticed is that arm motion might not be completely impaired, but weakness causes people to compensate in other ways rather than moving their arms to regain functionality,” says Shmuelof.

“Putting a research lab in a rehabilitation village makes a lot of sense,” says Bar-Haim. “There, we can go directly to the residents and ask them what their needs are. We can also test out our technologies, which we make sure are fun and pleasant, on the residents and get their feedback.”

That Immediate feedback appealed to Prof. Ilana Nisky of BGU’s department of biomedical engineering, who has joined Bar-Haim in developing a belt that helps stroke patients improve their walking. She is an expert in haptics, which is the body’s sense of touch. Their project is being funded by the Israel Innovation Authority.

“When you design medical devices, you need to think beyond engineering and understand how they [the patients] will be using the devices,” says Nisky.

“One of the most important elements in walking is being able to feel the ground and knowing where your legs are without looking at them. That ability, which we take for granted, can be damaged by a stroke. So, we are designing a belt that is worn on the person’s skin under their clothes that will massage the person’s waist and help them with their terra sense – the sense of where the ground is and where their legs are,” she explains.

“What is truly groundbreaking in our belt is that it does not need to measure where the legs are relative to the ground. Instead, we rely on an artificial intelligence algorithm that we train on many examples of past walking to guess where the ground and legs should be at a given moment in time, based on a very simple sensor that is placed on the belt and in the center of the body. This way the only thing the person after stroke will need is the belt itself.”

“What is truly groundbreaking in our belt is that it does not need to measure where the legs are relative to the ground. Instead, we rely on an artificial intelligence algorithm that we train on many examples of past walking to guess where the ground and legs should be at a given moment in time, based on a very simple sensor that is placed on the belt and in the center of the body. This way the only thing the person after stroke will need is the belt itself.”

The researchers have already developed a prototype, but in the future each belt will be customized to the individual person’s needs.

“We hope they will use the belt, and that the information it provides to them will be helpful,” Nisky says. “We also hope that if they use it a lot, then perhaps they will eventually be able to walk on their own without it.”

To make sure that they will indeed wear it a lot rather than buy it just to have it collect dust in the closet, the team also works with Ofer Canfi, a designer who graduated from the Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design and the Royal Academy of Arts, London, to make the belt look and feel nice, using advanced manufacturing procedures and hi-tech fabrics.

Nisky notes that now is the ideal moment for such research. Haptic devices have become much more pleasant to use. “It’s like a massage. What’s not to like?” she says, while artificial intelligence has reached the point where it can be harnessed for purposes such as physical therapy.

A future entrepreneurial hub

Another important advantage offered by the Negev Lab is its multidisciplinary nature.

“We have clinicians, clinician-researchers, engineers and programmers, all working together,” says Nisky.

Bar-Haim also envisions the Negev Lab as an entrepreneurial hub, a space where technologies from around the world can be tested and receive feedback from the people who stand to benefit from them.

In fact, this vision is already a reality. The Negev Lab collaborates with Swiss-based Mindmaze, which designs virtual reality and computer simulations. It sends its latest technologies to the lab, where Shmuelof puts them through their paces with patients.

One such program lets the patient control a dolphin on a screen by raising or lowering their arms. It has been a big hit with patients.

“Seeing the dolphin move in response to my arm movements shows me how much I have improved,” one says.

“Using the vest gives me hope that I will return to moving my hand easily,” another says.

“At the end of a treatment session, I feel like my whole body got into it,” says a third.

“People instinctively understand how to control the dolphin, and they enjoy it,” explains Shmuelof.

“The simulation makes me feel like I’m playing a computer game at home, and I just want to pass level after level,” says a patient.

That is encouraging feedback, because the Negev Lab wants to develop programs that people will actually use.

The rehabilitation hospital

In a welcome development, the ADI Negev-Nahalat Eran Neuro-Orthopedic Rehabilitative Hospital is nearing completion. Thanks to the support of multiple government ministries, JNF-USA and international donors, the hospital is set for completion late this year.

It will have more than 100 beds and will provide unique research opportunities.

“It will also be a unique research hospital, with an ethical and information technology infrastructure that will allow us to study most of the activities that will be carried out there,” says Bar-Haim.

“In other words, a large proportion of what goes on in the hospital will be able to be researched and incorporated into academic studies. That is not the case in most hospitals around the world currently, not even in teaching hospitals.

“Once the hospital is completed, the Negev Lab will move into its new space and become the largest and most advanced lab of its kind in Israel.”

Bar-Haim and Shmuelof are excited about the opportunities to advance their understanding of how to rehabilitate stroke patients using the knowledge they will gain from researching at the hospital.

“How active was the patient during the day? How well did she sleep? How long did she sit for? Measuring patients’ activity during the day will allow us to better understand how it affects their recovery, and to find ways to increase their activity during rehabilitation,” explains Shmuelof.

“We are already receiving inquiries from around the world about this new lab,” he adds.

The future

While the South has lagged behind the Center in terms of medical and rehabilitative care, Bar-Haim and Doron Almog’s vision does not stop at achieving parity with the Center, but, rather, aims to exceed it.

“We believe that residents of the South deserve the same quality of care as those in every other part of the country, and we believe that we can set the bar higher for rehabilitative care,” says Almog.

“This village was founded on the principle that a person is a person no matter what, and this hospital and research lab are finally starting to realize our full vision. In this place, all people will be provided with the best possible care and loved beyond measure.

“In the age of corona, the importance of the Negev Lab is clearer than ever before. Each and every day, our rehabilitation professionals empower people of all ages, backgrounds, and levels of need, giving them a new lease on life and returning them to their families in good health and renewed spirit.

“But we can expedite this process and make it even more powerful through collaborative translational research. There are so many people hurting right now, and the groundbreaking research being done at the Negev Lab can change the face of rehabilitative care across Israel and around the world.”

“I envision the Negev Lab and the ADI Negev-Nahalat Eran Neuro-Orthopedic Rehabilitative Hospital as the core of the future National Rehabilitative Institute of Israel,” declares Bar-Haim.

Original Post: https://www.jpost.com/health-science/bgus-negev-lab-is-bringing-stroke-rehab-into-the-future-675273