By Nathan Jeffay

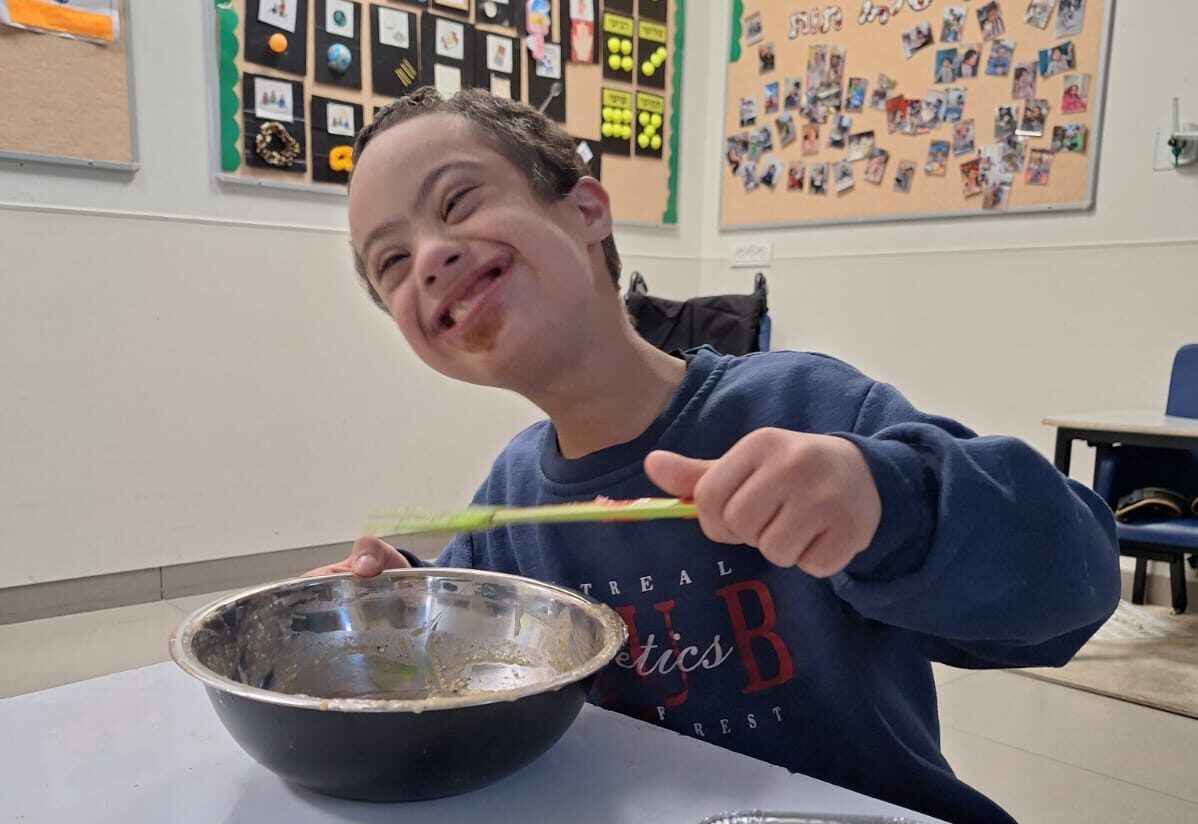

A staff member and a resident at the ADI Jerusalem facility for individuals with disabilities (courtesy of ADI Jerusalem)A rigorously sterile environment and other strict measures have helped ADI Jerusalem elude the pandemic, though staying safe has come at a cost of increased isolation

The parents gaze through a translucent sheet. Their kids cannot speak, but touch — in the past the main channel of communication during visits — is strictly prohibited, as it has been for nearly a year.

“The rules are clear, however much it’s upsetting: parents can’t touch the child,” said Shlomit Grayevsky, director of ADI Jerusalem, the region’s largest residential facility for individuals with disabilities.

“It’s very very difficult, and parents say, ‘we’re healthy, let us hug,’ but we just don’t know, and given these young people are in such a high risk group, we can’t afford to take chances.”

At the start of the pandemic, nonessential visitors, including family, were totally barred. Since June immediate relatives and a select number of others have been allowed to visit, but only outdoors and only after pledging to stay behind a sheet of plastic or glass at all times.

It’s a heart-wrenching price to pay for protection from COVID-19, but it’s working. Some 300 staff and volunteers are needed to keep the center running — many of whom need to engage in close physical contact with residents, who do not wear masks for medical reasons. Despite the large amount of traffic in and out of the center, no residents have caught the coronavirus.

Parents, though deeply saddened by the visiting rules, are relieved that the virus has been kept away from their children. “As the coronavirus continues to cast a dark shadow, threatening the whole world, this is the one unique place where the most vulnerable among us feel safe and secure,” said Yael Mazaki, whose son Yochai lives at the center.

Grayevsky, a nurse by profession who led intensive care teams at Hadassah Medical Center, Bikur Cholim Hospital and Shaare Zedek Medical Center, says her nursing background is responsible for her decision to enact “extreme sterility protocols,” credited with keeping the pandemic at bay.

“Every day I thank God for our success, and reflect on how we’ve managed it,” said Grayevsky, who took the helm of ADI Jerusalem 20 years ago.

Grayevsky said the success came from the center acting early and never letting down its guard. Every single person who enters, even if a technician fixing an air-conditioning unit without encountering residents, must first take a COVID-19 test.

“From day one we internalized that a big change would be needed in how we live, how we dress with the addition of protective gear, and how we act. We have added measures which make us far stricter than the law requires, including weekly coronavirus tests for staff,” she said.

Staff wear head-to-toe protective gear at all times — especially important as most residents are deemed unable to wear masks for medical reasons. Toys, iPads and pieces of rehabilitation equipment are constantly wiped down; hammock sling harnesses that move the residents from their beds to their chairs are washed after every use, rather than at the end of each day; and every classroom is constantly cleaned as learning takes place, rather than after the classes are completed.

There have been brushes with the virus. Recently, a teacher tested positive for COVID-19, and a third of the residents went into isolation. But there were no infections.

While residents do not wear masks, staff and volunteers do, creating a frustrating barrier in the efforts to connect with residents. “The youngsters here all watch our faces and follow our lips, yet suddenly our greatest communication tool has been covered by masks,” Grayevsky told The Times of Israel. “All of a sudden, we need to use our hands, our eyes and our voices in a way we didn’t before.”

Among the 100 people who live at ADI Jerusalem, from infants to age 38, some have a degree of understanding about the pandemic raging outside that keeps their normally tactile visitors out of reach. Others don’t.

The residents all have all multiple disabilities: a combination of physical, cognitive and sensory disabilities so serious and extensive that their parents can’t provide them with the high-level care that they require at home. All are immunocompromised and the majority have weak respiratory systems, which puts them at extreme risk should they catch COVID-19.

To fight the virus they are divided into three “capsules” that stay separate from each other. There is also a ban on crossover of staff and materials for education or therapy between the sections. And there is always a full team of staff on standby, in case a team is put into quarantine.

The capsule system requires twice as much manpower. The solution to this very serious issue has been the use of national service volunteers who live in the center for stints and allow everything to continue running without sacrificing the quality of care.

While placements for Israel’s national service program normally expect volunteers to be active for a typical 9-5 working day, here they can be on the go 24/7.

“It’s a profound and heartwarming experience to tuck the residents in at night and wake them up in the morning,” said Roni Mor, 20, who just finished a volunteering stint at the center. “I will cherish these memories forever.”

Residents, staff and volunteers recently received their first vaccine shot, though the measures are remaining in place for the foreseeable future, given the time it takes for immunity to kick in. There are also worries over the chance of reduced effectiveness against mutations of the coronavirus.

As measures have taken effect, staff explain each change to residents, stressed Grayevsky. “We speak to everybody and explain everything as if people understand all we have to tell them,” she said. “The level of reaction varies a lot. And if they react, while none of the youngsters can speak and none can express with words what they think and feel, staff can understand what is on their minds.”

But while residents still have the companionship of each other, and of staff, the facility has lost some of its buzz. The place has a strong ethos that emphasizes its centrality in the local community, at the main entrance to Jerusalem, and it is generally open for members of the public to visit, connect with those who live there, and volunteer. The Bnei Akiva youth movement normally has a chapter there for residents.

All this ground to a halt in March, and Grayevsky only plans to allow visitors again once contagion levels in Israel are rock-bottom.

Staff made a “Wall of Hearts” by the entrance for members of the public to leave cards, pictures and greetings, but it’s not the same.

“We were always proud that we weren’t a closed place, but always an open place that welcomed people from the community,” said Grayevsky. “It’s always been a hectic place with lots of life from the outside. Overnight, this stopped. This is really, really hard.”

Original Post: https://www.timesofisrael.com/100-residents-0-cases-how-jerusalems-largest-home-for-disabled-dodged-covid/